Today we welcome new writer Daniel Adamson to TFT. He argues that in an ideal world cricket and politics shouldn’t mix.

It would appear that memories of the bleaker aspects of cricket history have suffered somewhat of an erosion over time. It remains important that the darker historical lessons of the past century are acknowledged – and more importantly, remembered.

Throughout the twentieth century, as Cold War diplomats sat in stalemate around negotiation tables, international rivalries were played out in a number of literal and metaphorical fields. Olympic games in Moscow (1980) and Los Angeles (1984), along with the 1969 World Ice Hockey Championship, inter alia provided a stage for national tensions to be exhibited, if not resolved. Sport became a political tool.

Nonetheless, the role of cricket as a vehicle of political expression has been overlooked within broader historical narratives. Perhaps the superficial civility of the game has obscured the murky undercurrents of tension that, in reality, underpinned many of the sport’s twentieth- century contests. Whereas the animosity of the USSR and the USA could be slogged out in a series of violent sporting contests, the character and etiquette associated with cricket fostered an altogether more insidious agenda. The velvet glove of cricket’s gentlemanly customs concealed an iron fist.

The Bodyline tour of 1932-33 provided the first indication that cricket was assuming a significance that transcended good-natured national competition. As Douglas Jardine’s men hurled down bouncer after bouncer at their Aussie counterparts, an unprecedented sense of ill feeling between England and Australia was engendered. Remarkably, the situation became so critical that pre-existing commercial ties bonding the two countries began to break down in the aftermath of the Ashes series. Within Australia, a legacy was created whereby national identity became entrenched along the relatively trivial lines of sporting enmities. Such an effect has endured to the modern day.

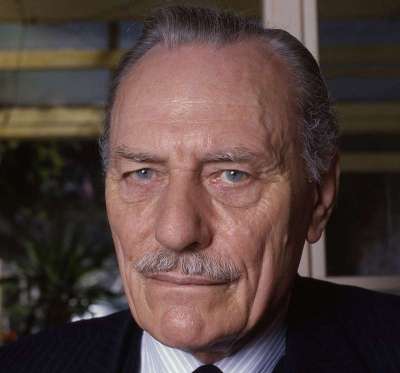

Worse was to follow. Just eight years after Enoch Powell delivered his “rivers of blood” diatribe, the 1976 series between England and the West Indies became an unprecedented opportunity for the visiting team. Through cricket, the tourists sought to challenge the prejudice experienced by Caribbean immigrants at the hands of their former colonial masters throughout time. England captain Tony Greig’s declaration that he intended to make the tourists “grovel” acted, albeit unwittingly, as a stark reminder of the sinister racialist foundations that still afflicted British society. A sporting contest that could – and should – have been an enjoyable cultural cross-exchange became a matter of political life and death. The formidable West Indian team were forced to utilise their beloved sport as a means of justifying their own international existence. Their resounding 3-0 series triumph, therefore, was made all the sweeter. However, achievements on the field could not mask the unfortunate proxy socio-political dimensions.

Similar effects were observable in subsequent encounters between India and Pakistan in 1987 and 2005, and cricket has played a notoriously prominent role in recent South African and Zimbabwean politics. Who can forget the World Cup being used by Robert Mugabe to legitimise his sinister regime? Alarmingly, China has also entered the game of political cricket in recent years. The Chinese government has bankrolled several Caribbean stadiums in return for the diplomatic derecognition of Taiwan’s national status.

One hopes that the politicisation of cricket becomes less pronounced in the future. A game grounded – more than most – in courtesy deserves better than to be despoiled by external disputes. Yet, it should not be forgotten that cricket’s often-jovial exterior conceals elements of a dark past.

Cricketers: stick to Sir Henry Newbolt’s old adage of 1892, which adorns the gates of Lord’s Cricket Ground – “Play up! Play up! And play the game!”.

Let’s keep the pitch for cricket alone.

Daniel Adamson

Daniel is a PhD student in the History Department of Durham University.

Daniel, your article covered different issues to those I was expecting and so I am not sure I fully understand the points you are advocating. On your conclusion “Let’s keep the pitch for cricket alone” I cannot agree.

Sport can play a significant role in breaking down barriers of prejudice and I would not wish to see that change. In my lifetime the main political issue facing Cricket was Apartheid South Africa. It was right that the International Cricket community isolated South African Cricket until that country changed. It was the will of the majority in South Africa. The banning of the SouthAfrican team in 1970 was the right one.

On the West Indies, I am not sure of the point you are making. Greig’s comment was disgraceful as he subsequently acknowledged. The West Indies team was always keen to prove in the 75 World Cup and the 76 tour that they were the best in the world. The motivations were no doubt stronger because of the attitudes of people in England then. The Black Lives Matter protests show to me, a middle-class white Englishman, that too many people have not learned the lessons from 1976. It is an example of when sport and politics can still mix for the better.

In India, there are many troubling signs of that country’s increasingly authoritarian policies and discrimination against Muslims and minorities as well as women. Will that become the next significant political issue for Cricket. India has closed down Amnesty International in their country now and I wonder how long it will be before the treatment of minorities in India becomes a bigger issue than in England.

I would love to have a world where “Let’s keep the pitch for Cricket alone” was possible but I am not sure that will ever be possible.

Pretty much every country will have a ministry of sport or equivalent so it is totally impractical to keep politics out of sport. Every committee that sits and decides on the future direction of the game is political, even your local county annual shareholders meeting. Party politics is a different matter.

I don’t know if you remember Dennis Howell, the labour minister of sport In the 70’s, but he’s the only one I would trust that I’ve seen to give a decision putting sport, rather than party line first. This was largely because he came from a sporting background and understood its priorities better. Since his tenure we’ve had a succession of anonymous ‘suits’ cowtowing to the party line.

If we accept the inevitable nature of political involvement in all aspects of life we can at least insist that those holding special office should be equipped with enough inside knowledge and commitment to defend their corner, even against party policy, which I suppose is why successive governments have gone for ‘suits’, just be a mouthpiece for officialdom. It would be good to get a well known sporting celebrity with a mind of his or her own appointed to plough through the diplomatic minefield and get to the nitty gritty. At present it’s all too easy for governments to appoint these anonymous party liners without opposition. The Ministry of Sport in this country is just a sideshow with no real identity.

Absolutely Marc. Dennis Howell – the nation’s first ever Minister for Sport – was ace, and did much to improve access to sport via the Sports Council and their inclusive ‘Sport for All’ campaign.

However, I would give Tony Banks some credit. He was at the forefront – along with Mike Marqusee and a certain Jeremy Corbyn – in forcing the ECB to confront institutional racism for the first time and, ultimately, the creation of ‘Hit Racism for Six’.

I’m afraid I never liked Tony Banks. Came across to be a sound-bite man. His campaigns and schemes always seemed more window dressing than substance. No legacy to leave for me.

You’ve missed the key point about Greig – he was a white South African, speaking at the height of Apartheid. He qualified for England but no one lost the significance at the time of his origins.

Secondly “politics out of sport” was the mantra of those opposed to the SA boycott – the England rebels used it as their apologia, as did those supporting the Springbok rugby tours of the age. The answer was of course “who brought politics into sport in the first place”.

No cricket against Australia until the current, disgraceful policies in Victoria are lifted!

Those policies could be about to get a whole lot worse if the so-called Omnibus Bill passes which will allow children to be removed from their parents for up to 30 months.

An interesting angle on cricketing politics concerns the Kerry Packer ‘circus’. At the time it was the hottest political potato along with apartheid, yet the entire West Indies team at the time were quite happy to volunteer their participation, despite it not being considered ligitimate test cricket. Their reason was they felt the only way they could prove they were the best was to compete against the best, most of whom at the time were signed up by Packer. They never complained about their time there and had a good measure of success. Indeed their only complaint has been that their records during that series count for nothing. Viv Richards has always maintained that his time with the circus was the most rewarding of his career.

What the above illustrates is that political interference, which Packer’s certainly was, is not necessarily bad for all. It certainly resulted in cricketers generally becoming better paid, though this was hardly Packer’s prime intention, he being a businessman and no altruist.

Packer was indeed out for himself, but the opportunity to outmanoeuvre (or shaft completely) the Australian board who had denied him broadcasting rights was the fact that players were getting a minuscule amount of the money cricket was raising. Thus by paying them a lot more he ended up also paying himself more. It was a generational clash too with the elderly men on the Aussie board being stubborn when it came to considering any form of change, and unable to see the sort of commercial opportunity for cricket that Packer could.

Yes well said everyone. I’d love to see Sport dissolved from politics but that’s unrealistic as has been pointed out. I’d add that the South African quota system that has almost ruined the South African Test team from a competitive point of view. That’s political as is Black Lives Matter, a rather iffy organisation in my view and Taking the Knee which I find rather distasteful for a number of reasons. But I’m not getting into that as James is not in favour of political arguments on a cricket blog, and rightly so.

I’m sorry but I find this article desperately naive and incoherent. To me this is an ill thought out argument searching unsuccessfully – bar South Africa – for supporting evidence. To cite Greg’s comment as an example of racism, for example, is nonsense. Greig was an intensely competitive guy trying to motivate his team for a difficult challenge against the best side in the world. I can see him making the same sort of comment had the opposition been Australia or anyone else. If he regretted his comments afterwards it was because we were stuffed, and as a result he looked a bit silly to say the least.

I hope your PhD thesis is better researched than this !

Greig himself was no racist, but he missed how his comment would be interpreted given it was coming from a white South African at the height of apartheid. It would therefore not have meant the same to Australians or NZ’ers.

James

I don’t recall there being accusations of racism at the time, although of course things were different in those days. As I remember, it wasn’t a considered comment, it was just something he came out with spontaneously in an interview and the racist accusations came later, but I could be wrong.

Thanks to Daniel for raising this interesting issue. Should politics be separate to sport? Do we want it to be? It’s incredibly complex.

My personal view is “I really don’t know”. Sportsmen are often in a position to use their popularity and profile to promote good causes. But then again sinister forces can use sport as a platform to legitimise themselves too.,

I should quickly mention that this issue is far too complex and nuanced to explore satisfactorily in a short blog. There are numerous examples I’m sure Daniel would’ve explored if this was a large essay (a point missed by many on Twitter). However, I’m encouraged by debate in the comments thus far which I hope will expand the debate.

The problem for sport, especially at international level, is that it has always been seen as a way a country can put itself on the map. This will always give it a political edge with polititions striving to take advantage of and credit for any on field success competitors might have, even though they’ve had no actual part in the process. It’s almost part of promoting their country’s cudos. The Olympics is probably the ultimate example of this, the way countries and even continents compete for the right to stage it.

Politics and sport are inextricably linked. Some examples:

Physical Education in the national curriculum;

Selling off playing fields;

ECB lobbying to have cricket removed from the ‘crown jewels’;

Tobacco sponsorship.

Currently maybe banning limited numbers of spectators from watching sport until some illogical fictitious date next March because there is a perceived risk of catching CV , when By any logic the risk is so low to be almost insignificant. Ok maybe I’m stretching it a bit far to be some sort of political motive, but I fail to see any reason for it, certainly not health and safe anyway. But that’s probably a separate discussion.

Very good article by Barney Ronay on the changes that are taking place in football.

Almost all of it applies to cricket too.

In which vein, I noticed this gem on the Cricinfo ball-by-ball commentary of T20 Finals day.

There’s a list of things that the ECB Technical Committee has to take into account when deciding how to shorten/reschedule matches in case of bad weather. The last in the list of priorities is this:

* To balance the desire to achieve commercial objectives with the need to ensure matches of as long a duration as possible.

I’m just gobsmacked that the commercial objectives of a cricket board would ever NOT involve playing the whole of a scheduled match, as this implies….

I was wondering about an aspect of this when I was reading the comments (to two articles here, and to others elsewhere, about T20) to the effect of “I don’t watch the IPL because it’s a bunch of mercenaries”.

But isn’t that true of county cricket too now? In the Blast quarter-finals, as far as I can see only two of the eight teams (Lancs and Gloucs) fielded more than about half a side of homegrown players, despite there being only four “overseas” players in the four matches–three of whom played in the same game. That game–the Leics v Notts game–featured only eight homegrown players between the two sides. Where do you look there for a connection with Leicestershire, Sussex, Northamptonshire or wherever?

Where do you go to see them, if you do at all? The “Cloudfm County Ground” (obviously the only ground that the county play on these days)…which could be anywhere in the country for the uninitiated? (It reminds me of having to look up the unfamiliar venue of a ODI in Australia a couple of years ago, only to find that it was–or at least used to be–the Bellerive Oval in Hobart, which has hosted international cricket for years!)

The geographical connections which Ronay is talking about in relation to lower-division football clubs are also dissolving in county cricket, it seems to me…and have been replaced by money connections–of various sorts.

Yes it is unfortunate that we allow so many cricketing mercenaries to come over and play in our white ball tournaments and then disappear after a few weeks. Even footie doesn’t allow that. It used to be that foreign imports had to play all season and we’ve had many great contributors over the years with players who have made England a second home for themselves and even married and had families here.

Whilst this may be true of many official overseas players , with some exceptions–and personally I’d like to see a minimum length of registration for overseas players and a maximum number per season–I was making a different point.

That was that even England-qualified players are much less likely to be representing the county of their upbringing, or their first county, than they used to be. It isn’t only the five-overseas-players-a-season type of movement, it’s that many if not most counties could easily put out a playing XI made up entirely of players developed by other counties.

That’s a huge change from a few decades ago. I can only think of three players from my childhood who represented even three counties; Ajmal Shahzad recently represented five in six years–none of which were described originally as short-term loan deals.