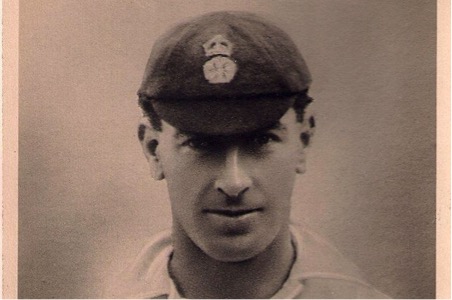

Walter Livsey (1893-1978) was one of the greatest wicket keepers of the 1920s. However, he never played for England. His career was halted by war, blocked by Herbert Strudwick, frustrated by injury, and ultimately curtailed by illness.

In 320 first-class matches, Livsey claimed 648 dismissals. And incredibly, in this ‘standing back’ age, 266 of them were stumpings. Strudwick by comparison effected 258 stumpings, but he played twice as many first-class games as Livsey.

Exceptional promise

Born in Todmorden, Yorkshire, Livsey’s parents made the move to Surrey while he was still a baby. Where, despite showing early promise as a wicket keeper he found opportunities limited by the presence of Strudwick. Therefore, in 1912 he was persuaded to make the move to Hampshire.

While qualifying for his adopted county, Livsey played a single match against Oxford in 1913. In the University’s colossal 1st innings score of 554, Livsey took 2 catches, stumped the top scorer and allowed only 3 byes.

In his first Championship match in 1914 he stumped Alan Shipman of Leicestershire, standing up to the fast medium in-swing bowling of Arthur Jaques. In that same summer, according to Wisden, Livsey caused ‘quite a sensation’ by stumping Jack Hobbs off a sharply rising ball from Alec Kennedy which swung wide outside leg stump. In total in his debut season of 1914, Livsey dismissed 62 batters (39 caught and 23 stumped) including 9 in a match against Warwickshire (4 caught and 5 stumped).

Wiry with immense nervous energy and extremely quick, but stylishly smooth in reaction and movement, Wisden observed that Livsey ‘showed exceptional promise’. With the outbreak of war this promise was put on hold. Livsey spent most of his war service with the army in India and was not free to continue his cricket career till 1920.

Strudwick’s successor?

In 1921 Livsey assisted in 80 wickets, 48 catches and 32 stumpings, more than any other wicket keeper in the country. In 1922 he was chosen in preference to Strudwick for both the Players vs Gentleman at Lord’s and the winter tour of South Africa. However, bad luck intervened. Immediately after selection, he broke the index finger of his left hand, a quite uncharacteristic accident for one who normally took the ball so cleanly, and whose hands were practically unmarked at the end of his career.

The fracture mended in time, but in only the 6th game of the tour, the 3rd finger of Livsey’s right hand was fractured by a lifting ball while batting. He returned home, missing the major part of the tour – including all the Tests. Despite being picked for 3 Test trials, twice on the England side, and 4 Gentleman vs Players matches, Livsey never go the opportunity to play a Test match, nor did he make another tour.

Wonderful batting potential

Perhaps Livsey’s name was passed over as he rarely had the opportunity to excel with the bat, usually coming in at number 10 or 11. Livsey, however was more than capable, in 1921 he joined Alec Bowell at 118/9 and together they put on 192, still a club record, as Livsey ended unbeaten on 70.

In 1922, Livsey was the ultimate hero of Hampshire’s most famous victory, a victory as a whole that Wisden stated to be ‘without precedent in first-class cricket’.

Bowled out for just 15 and following on 208 behind against Warwickshire, when Livsey came in at number 10, Hampshire were only 66 ahead. Livsey proceeded to share stands of 177 with George Brown and 70 with Stuart Boyes as he remained undefeated on 110 and Hampshire cruised to the most unlikely of victories by 155 runs.

Although Livsey had not made double figures in any of his previous 7 innings, the performance at Warwickshire demonstrated his ability to perform under pressure. Despite regularly batting at the bottom of the order, Livsey scored nearly 5000 first-class runs with 2 centuries at an average of 15. Strudwick never scored a first-class hundred and averaged just 7.93 in Tests and 10.88 in all first-class cricket. Duckworth, who made his England debut in 1924, averaged 14.62 in 24 Tests and 14.59 in first-class cricket, but he never scored more than 75.

Livsey was undoubtedly a victim of the eccentricity of his captain, Lionel Tennyson. As Harold Day, the England Rugby international who played with Livsey at Hampshire after the war explained:

“I admired him [Livsey] tremendously both as a man and a cricketer. In my opinion he was desperately unlucky not to be chosen for a Test. There was no better keeper and Lionel, with his maddening perversity, would never recognise Walter’s wonderful batting potential.”

The serious butler

Livsey was not only Tennyson’s wicket keeper, he was also his butler. He would lay out his clothes, run his baths and on a number of occasions lend him money for pavilion card games. The stresses of wicket keeping, together with keeping up with Tennyson’s frenetic lifestyle, often left Livsey totally exhausted.

Livsey took his cricket seriously, and he even gnawed at his batting glove anxiously before every delivery he received. Meanwhile, part of his speed as a wicketkeeper was down to his sheer nervous energy.

At the end of 1929, despite still being at the top of his game, Livsey’s health deteriorated and he never played first-class cricket again. He did, however, do great work teaching in schools and returned as an umpire leaving an enduring story of his relationship with Tennyson.

Batting in a charity match, Tennyson was clearly dismissed and it fell to Livsey to give him his marching orders. Reluctant to raise his finger in response to the raucous appeal, Livsey conveyed a message that Tennyson had always asked him to give to unwelcome visitors: “His Lordship is not in, I regret to say”.

Walter Livsey, the greatest wicket-keeper England never had, died in 1978 – the last survivor of Hampshire’s great team of the 1920s that included Tennyson, Mead, Kennedy, Brown and Newman.

Robert Meakings

Robert

What a fascinating article. I feel ashamed to admit that I was completely unaware of him – I had heard the anecdote in your penultimate paragraph but did not know the origin.

We have some great wicket keepers today who will never play for England as it’s more important to the modern selectors that they can bat than keep, so we get the likes of Buttler and Bairstow, ordinary keepers at best, who retain their place on their batting reputation. It’s taken a year or two for Foakes, a world class keeper, to get into the national side and this only because Buttler has lost his batting form. The pressure on him to make an instant impact or lose his place resulted in a less than perfect keeping performance, though he did bat pretty well. However we all expect Buttler to return to the fold this summer.

So as we can see Livsey lives on in the modern era.

Interesting article – I knew the name but didn’t know much about him.

In defense of Lionel Tennyson:

1) He was related to the poet.

2) Nobody doubted his pesonal courage – when many did doubt the English batsmen being routed by Gregory and McDonald. Tennyson famously slashed a fifty off them batting one-handed after injury sustained in the field. Curiously just over sixty years later two other Hampshire batsman batted one-handed – but Paul Terry and Malcolm Marshall had less success except in helping another player to a landmark.

3) He must have been less annoying than Mark Nicholas.

Most unlucky England player not to be capped in my viewing time is probably Ray East. A talented left-arm spinner who took over a thousand wickets at 25 plus was a decent bat and field he suffered from competition with Underwood and doubts about his character (too much of a joker). The most unlucky anywhere would be Vince van der Bijl followed closely by Franklyn Stephenson.

A couple of details from pre-WW2 cricket picked up from Haigh’s ‘The Big Ship’ that I never knew:

1) It wasn’t illegal to apply foreign substances to the ball until the early 1930s. Australian bowlers used to routinely use a resin that they said helped them grip the ball better.

2) Touring teams used to bring their own umpire until the 1900s. This stopped because an umpire the English intended to bring was going to call Australian bowlers for chucking.

I guess sometimes things just don’t work out …

Another anecdote from cricket in the 1920s courtesy of Haigh – Australian batsman Roy Park had the misfortune to make a golden duck on debut (bowled by England seamer Harry Howell) and was never selected again.

Most repetitions of the story claim his wife missed the innings because she was picking up her knitting which is almost certainly untrue – what they don’t mention so often is Park who was a doctor had spent in the night before in attendance at a difficult childbirth.

The ECB is run by people who don’t care about cricket. A governing body should be run by people who care about the game and the fans.