Today we welcome guest writer Shounak Sarkar to TFT. He looks at the future of cricket broadcasting and assesses the dilemmas faced by emerging cricket nations.

As COVID-19 keeps wreaking havoc worldwide, much of the sporting world has ground to a halt. Understandably in the grand scheme of things, the world of sports pales in comparison to people losing their jobs and lives. Nevertheless, as Keenan Malik expressed so eloquently, sports still represent “the most important of the least important things”.

Therefore, this pandemic actually presents a glorious opportunity for sports like cricket to reflect upon and re-jig its bloated domestic and international calendar. There is an urgent need for individual cricket boards to unite for the good of the global game and ensure that cricket as a sport remains accessible to all.

Boards need to think about long term sustainability rather than opting for the short-term cash grab to offset losses inflicted by COVID-19. One such dilemma is choosing between the pay TV, free to air, and streaming broadcast models. Whilst this issue is universal to all sports, it becomes particularly relevant for associate and emerging cricket.

Sell out and pay for it later

Dr Paul Rouse, an Irish historian who teaches at University College Dublin, has conducted a brilliant in-depth analysis on the pay TV model and its impact on sport. In his own words, pay TV companies desperately crave exclusivity, as it adds value to their model.

But this exclusivity comes with a hefty price tag. The likes of BT Sports, ESPN, Sky Sports & Foxtel obviously pass on these costs by charging large subscription fees. This not only hikes up the amounts paid to players in professional sports but also drives the creation of professionals in sports which were previously amateur.

Striking lucrative deals with pay TV companies is also a poisoned chalice for sporting organisations. To put it simply, pay TV simply cannot compete with free-to-air television when it comes to viewer numbers. The strength of universal public service broadcasting is that it provides equality of access to every community within a country. Many simply cannot afford the vast subscription fees charged by the likes of Sky, Foxtel and ESPN.

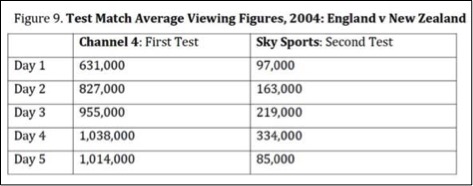

The evidence for this is crystal clear. Just look at the table below cited by Rouse.

These figures clearly show the impact of putting cricket behind a pay wall. The first Test between England and New Zealand in 2004 was shown free-to-air Channel 4, whilst the second Test was shown exclusively on satellite broadcaster Sky Sports. The first Test viewer numbers are 6 times higher for Day 1 and almost 12 times higher for Day 5.

At its peak, the 2005 Ashes on Channel 4 attracted 8.4m viewers. A decade later, the 2015 Ashes on Sky received just under 500,000. England’s dramatic cricket World Cup victory in 2019 attracted a peak audience of 4.5 million on Channel 4, as live international cricket returned to free-to-air TV for the first time in 14 years. If one adds up all the people watching cricket via streaming, Sky and Channel 4, the viewership peaked at 8 million – comfortably the largest cricket viewing figures in England in 14 years since cricket last appeared on terrestrial television.

The discrepancy in the numbers is undeniable. And it has real world adverse impacts on cricket. The Sport England Active People survey, conducted between 2008-09, found that 428,000 individuals aged 16 or over played cricket at least once during the season. A decade later, this has crashed by 32% to 292,200.

These numbers should terrify the ECB. And terrify they have judging by the ECB’s convoluted attempts to get cricket back on free-to-air channels. Indeed, the board have blown their cash reserves concocting an entirely new franchise tournament to entice the BBC. They now find themselves in a delicate financial position due to the coronavirus crisis and the resultant postponement of The Hundred until 2021. This example really underlies the importance of cricket exposure on mainstream television.

The choice for emerging nations

So what’s the best way forward for emerging cricket tournaments seeking exposure? Well, it’s a complicated question that does not have a simple answer. However, we can safely assume that a model which relies solely on pay TV to generate revenue and recoup its costs is not a successful long-term formula. Let’s consider the contrasting fortunes of the Euro T20 Slam and the European Cricket League.

On a cursory examination of the postponed Euro T20 Slam event, it quickly becomes apparent that it is very unlikely to drive engagement with local fans. The franchise team names are atrociously conceived, uninspiring, generic, and there is a distinct lack of tradition or tribalism. Furthermore, to this day, actual details about the tournament remain scarce.

No matter how much charity you extend to the Euro T20 Slam organisers, it seems more and more that the tournament itself was a cynical, money spinning exercise designed to capture as much TV audience as possible from the giant & lucrative Indian market. There was a distinct lack of “European” flavour in a supposedly European tournament. The Euro T20 Slam Draft event featured Bollywood & Punjabi Music and, to top it all off, the host for the night, Darren Gough seemed generally unfamiliar with most of the ‘local’ Irish, Scottish and Dutch cricketers.

Furthermore, in order to make the franchise model work, they offered over the top wages to marquee players such as Rashid Khan, Eoin Morgan, JP Duminy & Imran Tahir. The organisers GS Holdings therefore had no other option but to sell their content exclusively to pay TV. This included providers such as Sky in the UK and Star Sports & HotStar in the Indian sub-continent.

We have already witnessed how viewing figures drop dramatically when sports move away from free-to-air channels to pay TV. Without mainstream coverage on public broadcasting channels such as BBC One in Scotland, RTÉ One & RTÉ2 in Ireland and NPO 1 in Netherlands, the Euro T20 Slam will do little to raise the profile of cricket in these 3 countries. Sure, you will get some passionate & dedicated cricket fans through the gates but it is highly unlikely to capture the attention of casual observers or bring new fans to the sport.

By contrast, the European Cricket League gets many things right. ECL is the brainchild of global macro hedge fund manager and former German men’s national team member Daniel Weston. The founding of ECL is in itself a fascinating story which I recommend to readers.

The ECL mimics many aspects of the phenomenally successful UEFA Champions League football format, pitting the domestic T20 champions of several European countries against each other in a quick-fire group stage followed by a knockout competition. There are no expensive marquee players, no contrived creation of franchises. Instead, it gives local European club cricketers a chance to shine by building on the existing competitive structure and cricketing culture in UK & continental Europe.

Crucially, the ECL streams all its content for free through its sister European Cricket Network (ECN). This gives it the kind of accessibility that the Euro T20 Slam will never have. Furthermore, the inclusion of big name ex-Champions League & Eurovision executives like Thomas Klooz, Frank Leenders and Roger Feiner lends the project credibility.

The inaugural edition of the ECL in 2019 was a tremendous success. While the 2020 edition has been postponed due to COVID-19, I remain hopeful that this tournament will grow from strength to strength in the future. However, as good as free streaming coverage is, it is still mostly preaching to the converted. Free streaming ensures that the tournament is easily available to everyone worldwide, but unfortunately won’t be enough to pique the interest of the average ‘native’ European sports fan.

The problem is that non-cricket followers are not going to seek out streams of the ECL. If they don’t understand cricket, or aren’t even aware that such a tournament is taking place, then they won’t be watching. Consequently, getting local European broadcasters on board, particularly free-to-air broadcasters is vital.

To its credit, the ECL realises this. They have some ongoing discussions with local broadcasters in Europe and Weston is encouraged by the likes of the Catalan public broadcaster TV3, who featured the tournament and even added commentary in the local language.

Growing the game

Converting spectators into actual players is a different challenge though. And to tackle it, individual cricket boards in emerging countries across Asia-Pacific, Europe, Africa and the Americas need to take a 3-pronged approach.

1) Feature as much cricket as possible on local free to air channels.

2) Invest in grassroots cricket including facilities & equipment and get the sport into schools and clubs across the country.

3) Provide a pathway for the junior talent into the senior men’s & women’s national teams.

Phillipe Auclair, a French musician who fell in love with cricket after he moved to England, proposes another interesting strategy. In an excellent interview with Wisden Cricket Weekly, Auclair suggests that cricket could be sold to new audiences in the same way that Sumo was introduced to Europe: using the actual cricket action to explain what is going on rather than simply broadcasting games with generic commentary which assumes a level of prior knowledge.

Using such an educational approach might be a good way to overcome cricket’s idiosyncratic and somewhat impenetrable nature. Then, once a large enough base of cricket followers has been built up, associate nations can start streaming live games.

Another sure-fire method to spread the gospel, as well as potentially bringing extra government funding into the game, would be to make cricket an Olympic sport. Emerging Cricket founder Tim Cutler has emphasised this repeatedly on his podcast.

Is streaming the future?

There are many who suggest that the future of sports broadcasting lies in streaming. Indeed, many established pay TV providers around the world are struggling to retain consumers eschewing traditional TV subscriptions in favour of streaming gadgets and apps. Lower subscription costs (compared to Pay TV) and ease of access (being able to watch on portable mobile devices) are two of its biggest selling points.

Dedicated sports fans now want more bang for their buck and demand 24/7 access to broadcast-quality streaming. We see established TV providers such as Foxtel in Australia investing heavily in its subsidiary sport streaming service Kayo, to compete with the likes of Netflix, Amazon Prime and Stan. In New Zealand, the domestic cricket board recently signed a deal with a streaming sports service provider Spark Sport, which gave Spark the rights to broadcast domestic New Zealand cricket rights for the next 6 years.

When you look at trends in other sports, similar occurrences can be observed. In 2018, Amazon Prime signed a 3-year deal worth $130 Million US dollars, to stream Thursday night NFL games. They have since also snapped up the rights for streaming 20 live English Premier League matches every season, until 2021-22. Meanwhile, DAZN, a London-based online sports streaming platform recently won the rights for streaming 9 Bundesliga games for German & Swiss audiences.

Superficially, all these deals may indicate a revolution in live sports broadcasting; but a closer inspection of the deals suggests that it is not necessarily the case. Amazon’s 90-million-pound offering for EPL is similar to what BT Sports previously paid to broadcast 20 games per season. After a dramatic entry into the market, Facebook has also recently had to cut back & sign smaller deals with ICC to showcase cricket highlights in India and Major League Baseball in USA. All the evidence suggests that far from replacing the traditional TV companies, the emergence of streaming has just provided users with an additional way to consume live sports content.

There are also lots of downsides to streaming. NZ Cricket’s deal with Spark provoked fury amongst rural Kiwi residents, who complained that even with a fibre optic connection, an entire day of cricket will be a drain on their data usage and finances. The concerns are justified given Spark’s patchy & interrupted coverage of the Rugby World Cup last year, and Optus Sports’ well publicised FIFA World Cup streaming problems in Australia in 2018.

Nick Skinner, one of the co-hosts of the Emerging Cricket Podcast, has made some interesting suggestions in the digital realm. Nick recommends that the ICC look into developing something like a ‘Cricket Pass’ – especially for streaming associate cricket matches which often suffer due to low visibility & apathetic coverage. This concept is similar to an existing service in NBA called the ‘NBA Pass’ whereby customers can watch an entire season’s worth of games for something like $28.99 USD a month.

However, whilst this is a clever concept and great for existing fans of cricket, I remain sceptical of its usefulness in attracting new fans to the game given that a paywall remains. As mentioned earlier, those unfamiliar with cricket are unlikely to seek out games or shell out money to access coverage.

Getting the right balance

Whilst it’s true that consumption of digital content has skyrocketed over the last few years, it must be remembered that free-to-air TV still remains the most effective way of reaching people all around the world. If an emerging cricket board is serious about growing the game within its national boundaries, terrestrial coverage is non-negotiable.

Traditional cricket nations are different. They can afford a hybrid portfolio of pay TV, streaming and free to air coverage because cricket is an established part of their sporting culture. As long as some form of visibility is maintained on free to air networks, the sport is always likely to survive (if not exactly thrive) in these countries. Unfortunately, emerging cricket nations don’t have this luxury.

Association nations therefore face a starker choice. Taking a quick cash grab with pay TV or a paid streaming provider might seem attractive in the short term but it risks the longterm sustainability and survival of the sport in their country. Digital engagement & streaming content can still play a valuable part but they must be accessories to free to air coverage rather than replacements.

Shounak Sarkar

I’ve always felt that international sport should be freely accessable to all. You should be able to watch your country’s national teams on terrestrial TV for nothing. It should be written into the constitution as a democratic right and not subject to any kind of monopoly. Whilst I admire Sky and their fellow sporting specialists for their work in bringing us a wide variety of high quality live sports coverage, which they would still be able to do barring home country internationals, it is not in the public interest to have to pay special subscriptions to support their national team or go to pubs and clubs, where there’s a lot of distraction, to watch events they would prefer to see in the comfort of their own homes.

It would be hugely popular with the public, so what is the problem for the polititions voting for it?

I can’t believe Sky and their like have the influenece to pressure the government significantly.

As a post script I can understand why terrestrial TV dropped live test cricket as its length makes it disruptive to schedules, but what about a public service sports channel incorporating this. Just up the licence fee a few quid to pay for it. It could operate like BBC4 with limited hours. Just open the channel when there’s live international sport, then other terrestrial channels can show the highlights.

Whilst the general direction of the article is sound, the implication that the decline in playing numbers (in England, since those are the numbers cited) is wholly (or even mainly) down to the absence of cricket from free channels betrays a simplistic and mistaken view of the past.

The decline in club cricket was hugely accelerated (if not incepted) by the removal of most cricket from state schools. The selling off of school land and the reduction in school budgets – especially under Thatcher but continued under governments of all colours – removed the feedstock that the club system relied upon. When I first played senior club cricket in the early 70s I played for my Old Boys team (I went to a state school), and many of the teams in the area were of that type (although they had abandoned any exclusive requirement to have attended a particular school). Since then a huge number of those clubs have ceased to exist, in many cases because the school XIs no longer exist and provide a supply of new players. The effect of this is still driving a reduction in player numbers today. I am still playing, having been introduced to cricket through the school system, but when I retire from playing there will be few replacements for me from that source.

No doubt some will point to the various initiatives to encourage junior cricketers through club initiatives, and they are to be applauded, but many are too recent to stem the bleeding and (to be honest) the loss of interest from a voluntary club scheme is far greater than when players with any talent were forced to play for the school until they left. If you lose a player from junior club cricket at 10 or 12 or 14 you will never get them back. In the past a player who made it to 18 in the school system had every chance of continuing in senior cricket.

There is no easy answer to the problem. We have to accept that the days of school cricket are mainly over (and I live in an affluent area of Surrey which should be able to support it if anywhere can). But it does no favours to thinking about the issue to pin the decline in playing numbers elsewhere (although factors such as the tv issue have not helped). This can be easily seen by considering the optimum tv solution. If it is marginal to playing participation it is probably best to maximise tv income. If it is central to playing participation then prioritise viewing numbers. Regrettably I would go for the former, because i think using surplus income to support the junior game is probably more likely to succeed than hoping young viewers will convert to players in sufficient numbers.

They sold off the playing fields before 2005 I recall. The pay wall was another nail in the common.

I agree James. But my point was that players introduced through school cricket in the 1970s (or 60s in my case and late 50s for our oldest playing member) are still around and, as they retire they are not replaced further eroding playing numbers. In our 3 teams we have at least 6 still playing regularly who were introduced to the game via school cricket before 1980.

Hi Andy,

Thanks for your comment. You raised a lot of good points.

My main focus, when writing the article was to write from a broadcasting perspective; therefore I concentrated on fleshing out the free to air vs pay TV vs streaming arguments.

Towards the end of the article, I do mention that getting cricket into the schools system & providing a proper pathway into the senior men’s team is important. In fact, both cricket on terrestrial TV and cricket in schools go hand in hand.

Ive seen young kids from many emerging cricket nations such as Scotland, Netherlands, Thailand, USA bemoan the lack of cricket coverage on terrestrial TV. You need that exposure to get governments interested in investing into the game & also to get sponsorship.

I seriously disagree with you that investing all that SKY TV money into youth cricket, is having a tangible effect. What will kids aspire to, if they cannot see their heroes on TV?

Also, how do you get non-cricket fans interested in the sport, if its hidden away behind a paywall?

Thanks Shounak;

please do not think I agree with a paywall. It has been unhelpful and all we disagree on is the extent of its impact. I do not know the answer to the problem of participation. We are not going to reverse changes in schools or the wider socio-economic factors at play. One interesting point is that cricket is not unique. Your stats show participation in cricket declining by 32% between 2008 and 2018. Even football had a decline of 19% from 2007 to 2015 (by FA figures). This suggests to me that socio-economic factors are paramount and that the cricket authorities have exacerbated the situation by their policies.

Hmm… that is very interesting indeed. Was not expecting a downturn in football participation as well. It seems so ubiquitous in the English sports media landscape. I wonder if less and less children are participating in active sport these days, as a general trend?

Still compared to cricket’s 32% downturn, a 19% is only half as bad.

Football has been dying for 20+ years too… all sports are dying in participation.. cycling will claim to be growing but that was off the back of 2012 and will be falling away by now (unless they are so desperate to claim commuters as avid cyclists

The fact football is dying shows you that formats like 2020 won’t help the game survive as people won’t fit in 90 mins of sport let alone 2020, winnlose or draw games become all irrelevant

I was teaching in state schools before, and after, 2005; I can agree that the selling off of playing fields was damaging for all school sport (not just cricket), but other relevant factors include the cutting of school budgets as regards grounds (e.g. pitch) maintenance, the introduction of the National Curriculum (which made it more difficult to take pupils out of class to play matches), the introduction of OFTED Inspections which made staff who were (like me) essentially subject teachers fearful and so we had to concentrate on our subject, not on extra- curricular activities like sport, and school league tables (results became all that mattered to school leaderships, Governors and some parents).

With this multi pronged attack on our game we REALLY needed cricket to continue on live, free to view television. The fact that the ECB decided to sell the family silver at that point was, and continues to be, disastrous for the future of cricket.

Before 2005, I noticed that cricket had a much higher profile amongst pupils than it did by the time I retired in 2013. I’ve no doubt it is even worse now.

Thanks for your comment Giles. That is quite depressing to read. What the ECB did by putting cricket completely behind a paywall, amounts to criminal negligence, in my opinion. If they really needed the pay TV cash, I don’t understand why they did not go for a shared model, where Free to Air TV still showed come cricket. After all, some cricket is better than no cricket!

Giles Clarke’s reign as ECB Chief was disgraceful. He was also involved heavily in the Big 3 Takeover of ICC in 2014. What does big bucks from Sky matter now, when in the long term, people lose interest in cricket and participation drops off a cliff?

Now, in 2020 the ECB have a golden chance again to capitalize on the good press coverage that cricket received due to the World Cup win and that Stokes innings at Headingley. I sincerely hope that they don’t screw it up again.

BTW, had a question for you. As a State School teacher until 2013, did your school receive a visit from Chance to Shine? And in your opinion is the Chance to Shine charity making any real difference in getting state school kids interested in cricket?

I don’t remember hearing the ‘Chance to Shine’ was working in any of the schools I worked in after 2005 – but a quirk of my career was that I spent the last few years working on a succession of short term contracts covering maternity leave or similar in different schools and so I didn’t really get into much extra-curricular sport etc as I was only there for a limited time. Quite different to the 1980s/early 1990s when I, like many (most?), teachers got involved in sport (or drama etc).

Hopefully ‘Chance to Shine’ is making a difference, but as someone who got ‘into’ cricket through watching it on the BBC in the 1960s/70s, unless you have parents keen to support your interest I wonder how young people without Sky ever really get introduced to the game.

Chance to shine is an utter disaster. Sur eit goes into the odd school but it’s jut a mess about once a week and kids forget it …

It’s a good job for the boys though and good PR

Thoughtful and well-evidenced article – but I fear it is 5 months, if not 5 years, out of date.

One major problem is the assumption that the major boards want to grow the game. Whatever their rhetoric, their behaviour supports the view that they don’t. They dream of the game taking off in the USA but otherwise don’t give a damn.

A second major problem is the assumption that covid won’t change anything much. Constant repetition about “the new normal” suggests something else. Major economic hardship lies ahead with probable second wave extended lockdowns and who’s going to be able to afford sports’ channel subscriptions then?

You want a vision of the future… Chennai Superduperkings beat the London Invincibles (who didn’t live up to their name) in the final of the global franchise competition now named the Ashes. The stadium was empty because it’s too dangerous to have real spectators and most people were too scared to go anyway although those watching on-stream experienced a virtual crowd. Players are now openly permitted mental and physical enhancements. All the players have been on “elite pathways” since the moment of conception. Commentators marvel that sport used to be played between nations with their dangerous rivalries and unequal resources and celebrate how much more progressive this franchise model is.

This and more is the brave new cricketing world. It won’t all be in place next month but it’s closer than many realise.

Your cricket dystopia has no more reason to come true than any other projected view based on current trends. Trends like viruses die down. What we don’t know is how the world is going to view cricket after coming out of lockdown but enthusiasm from fans ought to be playing a part. Cynicism and fatalism that monetary trends will continue could be wide if the mark. What we need is passion for the game and imagination how to look at the future. Fans ought to fight for how they want the game to be played not concede that the world is irredeemably broken because of the last 40 years. Time to rethink. Where’s the energy to get things moving? There’s no lost cause. There’s a world to be remade if you are young.

Sadly whilst I don’t think Si’s vision is fully true the game has gone. The reasons for falling participation are varied and sadly open to much debate , here is my take

Removal of cricket from schools

This removes the mass participation and hooking of players . Current things rely on parents who already have an interest brining kids along.. that’s like the R rate!! If one parent brings one kids it’s not growing.. all you need are some not to stay or bother and the R rate drops (aka the game shrinks)

Paywall

This hurts from the POV of peoooe not seeing the game. It would be easy in modern streaming to simply broadcast games out individually and not have a ‘channel’.. how do we pay for it ? Etc etc

Amateur game

Has become more ‘professional’ (not really but makes out it is) which whilst sounding good makes it overall more of a chore. The money sloshing about in amateur cricket to subsidise first teams or paid players and overseas makes it less inviting and has pushed forward many many limited ability players as paid. No real positives to this

Formats

This is a hard one as it’s been drummed into people that ‘everyone’ prefers the shorter hittier games. From my experience that’s untrue. What’s actually happening is people have less time so compromise on playing 2020 in the evenings and sack off a full days play sat/sun. Not because they prefer it, in fact many don’t at all but it’s all they can fit in.

What we need to do is offer games to cater for all whilst making it obvious which formats are the pinnacle. Like pro… tests are the pinnacle and the closest we have are draw games so that’s what we should have saturdays . Sundays should be win lose cricket and then evenings should be 2020. That way, there are games and formats for everyone to pick their poison. All can be in leagues and so ECB affiliated and count as participation numbers.

It really isn’t hard. Then you will provide cricket for every type of player, every budget (2020 on astro etc) and also you’ve got the formats for the different skills to be developed.

Socially we have changed.. until March 2020 everyone had less and less time and so the first things to go over the last 25 years has been sport. That simply will not change regardless to whatever scheme or format you come up with !!! Covid has shown us that our biggest problem is that we don’t have the time to invest in ourselves, our families and hobbies.. maybe that’s the new normal we should be aiming for!! One where we work less and ‘play’ more!!

Cost

The cost of cricket is ridiculous now.. bats are 250+ for anything half decent .. pads 100, gloves 100 etc etc .. match fees high for any half decent ground… astro is dire to play on so reserve it for 2020 thrash abouts where bowling doesn’t count .. how do we bring the price down whilst keeping lovely tracks and grounds to play on ..

Wickets

With the professionalism era , wickets are becoming boringly flat… whilst it sounds good, looks pretty.. the skills needed decline due to being able to just thrash through the line of the ball… maybe whilst we don’t need crap wickets but more sporting ones to keep the game interesting ??

Using Good balls!!! Many games and leagues use utter crap balls.. barely move, don’t seam and are a dog ball within a few overs .. maybe using decent balls will help it swing for longer, seam for longer and keep shape and shine for longer ….. downside.. cost

Generally agree but must question some of the kit comments. It is still possible to buy a decent bat for half the £250 you quote for a bat. Just buy in the closed season sales and go for the lower (not lowest) willow grade. My experience is that the difference in grade is almost wholly cosmetic. My current Kookaburra Blade is in its 6th season (and looking good). It cost me £115 in the sale a few years back. No doubt facing 2nd team dobblers has helped, but it has also held up to 1st team opening bowlers. And as for paying £100 for a pair of pads or gloves; completely unnecessary even at top club level.

Liked the comment about paid players. We lost a 17 year old to a neighbouring club when they offered him an amount (can’t remember how much) for every run he scored or wicket he took – and he was nowhere near pro (or even premier club league) standard.

Cheap bats are fine but I can tell you I get mine from a bat maker (refuse to use big brands) and whilst I get them for less than 250 .. the same bat would cost someone else 350.. however!!! It does make a difference.. I lean on a shot and it flies.. when I use a 200 quid kook.. whilst it still is decent.. it doesn’t go half as far or fast!!

Looks are unimportant and are purely cosmetic.. performance however… there is a value on a performing bat

Yes, it’s why I have zero sympathy for clubs currently as they seemed to have loads of cash for covers, boundary ropes, paying overseas, paying coaches, paying players and subsidising first team players /kit etc

If you can do that, you can’t moan or kick up about missing 2020. Plus, you’re part of thr problem in amateur cricket not solution

The Blade is the best bat I have had in 50 years, and I have owned or used them all. 2lb 8oz and the ball comes off the middle even better than my old Newbery from the 80s, which weighed 3lb and was top of the range at a time when Newbery were far ahead of all other makers. Only downside is that, as a light bat, it is less forgiving if you do not hit the middle.

Do not conflate clubs buying things like covers with paying players. Last year we bought a brand new set of pro covers. They cost us just over £400 after the 90% grant from the ECB (total cost £4400) and proved themselves very quickly by letting a game go ahead which then produced match fees and bar takings which paid a half of the £400. If clubs are too lazy to use the various grants I have little sympathy for them.

You’ve totally missed the point but oh well

I seem to have responded to precisely the points you raised. Please explain the points you intended to make.

As to the participation debate I don’t think we have to look any further than the rise of the computer game culture since the 1980’s as the common factor. Kids would rather sit in their rooms role playing fantasy heroes than actively participate in something where failure is as likely to result as success. The rise in participation of women’s sports is linked to this, as the the gaming culture is almost exclusively male. Games are now produced as much for adults as kids to keep the addiction fed.

If these opportunities had existed when I was growing up would I have embraced them in the same way. I would like to think not, but who is to say. Their lure is undeniable. I have played championship manager games and they are addictively time consuming.

I did not expect the participation numbers even in football to be going down. Maybe it’s because people today are looking for a comparatively safer option to secure a long-term income source in this ever increasing competitive job market and even the expectations to get to a certain standard are higher in sports making it a less stable option. And as mentioned here, there is less money available for amateur players who are still developing.

And talking about growth of cricket, I think that making the whole system at the highest level (international cricket) more inclusive is the first and foremost need. Free to air TV networks showing matches is a good thing but it alone won’t help much in nations where cricket is relatively unknown and/or has to compete with other sports as well. Netherlands and Denmark in Europe have been around for quite some time now but in both the cases but the participation of local indigenous people has either decreased overtime or just remained somewhat stagnated. And they have Football and Hockey to look forward to. If local populations will not hear any Irish upset kind of story, it’s hard to inspire them to take up the sport seriously. Nepal and Afghanistan may have taken advantage of easy availabilty of televison coverage of cricket matches being staged in their neighboring powerhouses and the fact that they have not been significantly successful at any other major team sport are two major factors that Cricket has caught up with the locals.

So, current half-hearted approach of ICC to promote the game – where even the preliminary matches of the main event for which associate teams have to fight through a series of regional and global qualification matches over a period of several months are not even precisely acknowledged by the commentators themselves and regarded as segregated from the ‘main event’ i.e., Super-10s or 12s, is not going to help. It’s like ICC giving a few pathways to these nations and snatching back a larger chunk of opportunities from them just for pleasing some wealthy member nations.

When a happens (a=sport behind a paywall) we can’t automatically assume that the result b ( a drop off in viewing figures) is the caused solely by a.

As society changes, so will the past times and interests of that society. Issues such as poor facilities, travel and length of game time, employment constraints, cost, university involvement, issues surrounding race and many others have an impact on sporting demographics. There’s a huge danger that the easy way is taken when this subject is considered.