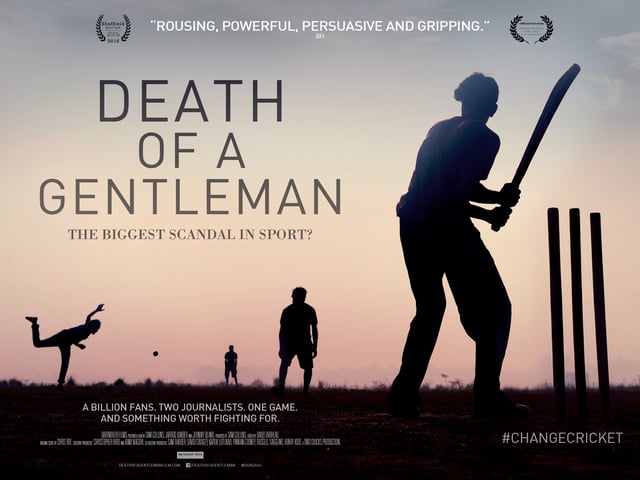

If you couldn’t care less about the future of cricket, don’t want the sport to grow, love private members’ clubs and think Giles Clarke is more of a cuddly teddy bear than a walrus, then Sam Collins and Jarrod Kimber’s new film Death of a Gentleman isn’t for you.

If, on the other hand, you actually want test cricket to exist in twenty years’ time, value transparency and equality, want cricket to expand and abhor secret deals in hotel rooms, then you must see this film when it’s released on August 7th.

Death of a Gentleman is probably the most important film ever made about cricket. Why? Because it’s actually trying to fix the major problems confronting the sport we all care about. What could be more important than the future of the game itself?

On the surface, a film about cricket administration seems about as exciting as rice cakes. But this isn’t the case at all. If you care about cricket, your appetite for this honest, frank and extremely worrying documentary should be enormous.

It’s a story of greed, corruption, ineptitude and intimidation – an intense and thoughtful look at how sportsmanship and a sense of fair play no longer exist at the ICC. Rather than serving the interests of the game, each ICC member is simply looking after its own.

The film reveals an absolute tragedy: that the people governing cricket neither have the appetite nor the wherewithal to govern the game fairly, in the interest of all its members, for the benefit of the global game. The evidence presented is damning.

According to Collins and Kimber (and I imagine most cricket correspondents feel the same but don’t have the freedom to express it) the individual national boards only care about maximising the commercial value of the rights they hold. The other boards, the supporters, and even cricket itself, can go to hell.

The film begins with a trip down under to meet likable former Australia opener Ed Cowan – who, interestingly enough, was Steve Finn’s last test wicket until last week’s third test. At this point, the film only intended to ask a related, but not so contentious question: is test cricket dying?

Cowan talks emotionally about his dream of playing test cricket, and fulfils a lifelong ambition when he strolls out to bat with David Warner at a packed MCG on Boxing Day. It’s the traditional steady opener who occupies the crease alongside the archetypal modern dasher. It’s old meets new.

Sam and Jarrod feel that Ed embodies the spirit of test cricket. While young men still dream of wearing the baggy green and claim, like Cowan, that “test cricket is the game”, there’s surely hope for the longest and purest form of the sport?

Their perspective soon changes however. They travel to India to watch the IPL (“cricket Bollywood”) and encounter a passionate stadium of Indian fans cheering on an artificial franchise. It’s gripping; it’s a spectacle; the crowd are delirious. Will T20 cricket, the brash younger brother, eventually consume the dignified gentleman?

But just as they’re reaching some kind of conclusion – with the eloquent Australian journalist Gideon Haigh describing T20 as a Haiku version of literature – a much bigger story emerges: Sam and Jarrod stumble across a sporting scandal as mindboggling as anything going on at FIFA.

The scandal, of course, is the so-called ICC ‘restructuring’ – better described as an unabashed power grab – of 2014. Sam and Jarrod discover, to their horror, that this deal was first discussed by the BCCI, ECB and ACB in secret, in a hotel room, miles away from ICC headquarters, in a meeting where no minutes were recorded. This is how the people who run cricket do business folks.

As a result of this ‘restructuring’, India, England and Australia were appointed as the only three permanent members of the ICC’s new Executive Committee. They were also granted over fifty per cent of the ICC’s total revenues – leaving the other relatively impoverished national boards (who already had financial difficulties) with peanuts.

Suddenly, instead of asking whether test cricket can survive in the modern world, Sam and Jarrod are forced to ask much bigger questions. Does cricket make money to exist, or does cricket exist to make money? Why is everyone desperately seeking power, and doing their utmost to keep hold of it, when the ICC is supposed to be a non-for-profit organisation? The plot thickens into a sinister gloop.

I guess most of you are wondering how the BCCI, ECB and ACB got away with this dastardly manoeuver. They’ve made cricket more secure in their own countries (in the short term at least) but what about the other seven test playing nations and the 95 associate and affiliate nations? It’s the ICC’s job to represent and protect all these nations not just line their own pockets.

After speaking to players, ex-players, broadcasters, journalists, administrators and whistle-blowers over a three-year period, Sam and Jarrod conclude that the ICC operates exactly like a private members’ club rather than a modern, progressive sporting body. But don’t just take their word for it: this was precisely the conclusion reached by Lord Woolfe after he conducted the ICC’s Independent Governance Review in 2012. You can download the report here.

Woolfe, who expressed his dismay at the Big Three coup last year, bemoaned the complete lack of transparency, accountability and a deplorable lack of ethics at the ICC. As for those outside cricket, here’s what Gideon Haigh says: “cricket exists for broadcasters and sponsors” while fans are merely there to be “exploited”. It’s pretty gloomy stuff.

Two of the main characters at the heart of the scandal are obviously India’s N Srinivasan, who remains ICC chairman even though the Supreme Court of India ordered him to step down as BCCI President last year, and our very own Giles Clarke. One gets the sense that the former is an extraordinarily shrewd operator.

Here are some facts about Srinivasan. His company, Indian Cements, owns the Chennai Super Kings – one of the most lucrative, popular and successful IPL franchises. Chennai’s captain, a man called MS Dhoni (ring any bells?) was even made a vice-president of Indian Cements.

Consequently, the President of the ICC, a body that is supposed to protect test cricket and act impartially in the interests of the whole sport, has a huge interest in a major IPL franchise. The expression ‘conflict of interest’ was surely made for situations like this.

Meanwhile Srinivasan’s son-in-law, Gurunath Meiyappan, who was Chennai’s ‘team principal’ (i.e. the head honcho) was recently arrested for illegal betting and passing on inside information to bookies. He was found guilty of bringing the game into disrepute and banned for life last month.

Now let’s move on to Clarke. Death of a Gentleman doesn’t need to portray Clarke as arrogant, aloof and pompous because cricket fans already think he is. Having said that, he plays up to his pantomime villain status beautifully – or should that be nauseatingly? When I went to the press screening of the film, many in the auditorium actually booed when Clarke appeared on screen.

When asked about the Woolfe report, Clarke sneered angrily at Sam: “Woolfe doesn’t know what the ICC is”. When asked about Alan Stanford, Giles’s repost is brimming with contempt: “It’s history … it’s irrelevant … next question”. Clarke reveals his true agenda, however, when his motivations are questioned: “I have to put my board’s interest first”.

Do you really, Giles? Isn’t there a bigger issue in play? The ICC is supposed to look after world cricket. Who cares if England are the best team in the world if only three countries have the means to play cricket to a high level?

And what about our interests Giles? That’s the desires of the ordinary cricket fan. Did you ask the English cricketing public whether we supported your shameful coup? Of course not. It’s our job to buy tickets and fork out for our Sky subscriptions. We’re not supposed to question authority. You want us to shut up and trust you, but why should we? Most-fair British people are appalled by the ECB’s role in the great ICC power grab.

Just remember this folks. The next time you read a good news story about the ECB investing in grass roots cricket, women’s cricket and other benevolent initiatives – all of which are brilliant and extremely worthy causes – just remember that there’s less in the pot for men’s and women’s cricket in places like Sri Lanka, Pakistan, New Zealand, Ireland and even Afghanistan. Cricket has finite resources. There’s only so much money to go around.

Jarrod and Sam do an excellent job of tracing the activities and motivations of the ICC’s private members’ club. They try to gatecrash secret meetings; they follow the money; they unravel Srinivasan’s web of power and influence. Things even get a little tense at times: as a result of their efforts, Jarrod’s press pass is revoked and there are some clumsy attempts to intimidate them. Apparently exposing ICC corruption isn’t good for your health or your career.

Even those formerly at the heart of the ICC are seemingly punished for stepping out of line. When Haroon Lorgat (the former president of the ICC who commissioned the Woolfe Report) is appointed by Cricket South Africa, the BCCI retaliated by cutting short their tour against the Proteas and arranging new fixtures against the Windies. The message is clear: don’t mess with the big boys.

Of course many of you know all this already. It’s no secret that cricket’s multi-billion dollar economy serves three nations while the rest struggle against the rising tide of bankruptcy. The big question is this: what can ordinary fans like us do to stop vested interests from killing cricket?

Here’s what we can do. We don’t let cricket administrators off the hook. We keep up the pressure. We keep asking all the relevant questions that Sam and Jarrod’s film begs us to ask:

Why is cricket the only sport in the world that doesn’t care about growth? While rugby and football are doing what they can to expand their world cups, cricket is shutting the door on associate and affiliate nations by reducing the 2019 World Cup to ten nations. For all the corruption at FIFA, at least Blatter and Co are trying to grow the game.

Why are the big three so reluctant for cricket to appear at the Olympics? This idea won’t appeal to everyone but I ask you to think about the issue broadly. Olympic sports receive government funding. The smaller test nations and developing countries really need these extra resources.

Finally – and this is possibly the biggest question of all – why do cricket fans tolerate governing bodies that are neither accountable nor transparent? It’s simply not good enough.

Unlike professional journalists, who need to keep the authorities onside to a certain extent to do their jobs (i.e. to maintain their access to players and information etc) us bloggers and supporters owe the authorities nothing. We’re free to do and say what we feel. So let’s bloody do it.

Obviously we can’t expect a revolution. I doubt Jarrod and Sam will gather an army of protestors, scale the walls of the ICC and make Monty Panesar or Fawad Ahmed the new President. However, when I spoke to Jarrod about his film yesterday (you can hear the full interview here) he did articulate a realistic aim …

Srinivasan and Clarke won’t be around forever. If we can keep the pressure up and influence public opinion, it will force future officials to take us seriously. The next generation of administrators are yet to shape their worldviews. They are still open to new ideas. By putting a collective campaign for better governance at the heart of cricketing discourse, we might just alter the psyche of the next Srinivasan and Clarke.

The best way to get cracking is to visit Jarrod and Sam’s site www.changecricket.com and sign their petition. Use the hashtag #changecricket as much as possible and keep the conversation going.

I implore you to watch Death of a Gentleman, of course, but don’t stop there. Tell others to watch it too. Tweet about it. Facebook it. Retweet articles like this one. Write your own article. Hell, why not start your own blog and help the cricket community to hold authority to account? The more chat we can muster, the more we’ll ramp up the pressure.

Tell the world how sick cricket is. We’re not as powerless as you might think.

James Morgan

@DoctorCopy